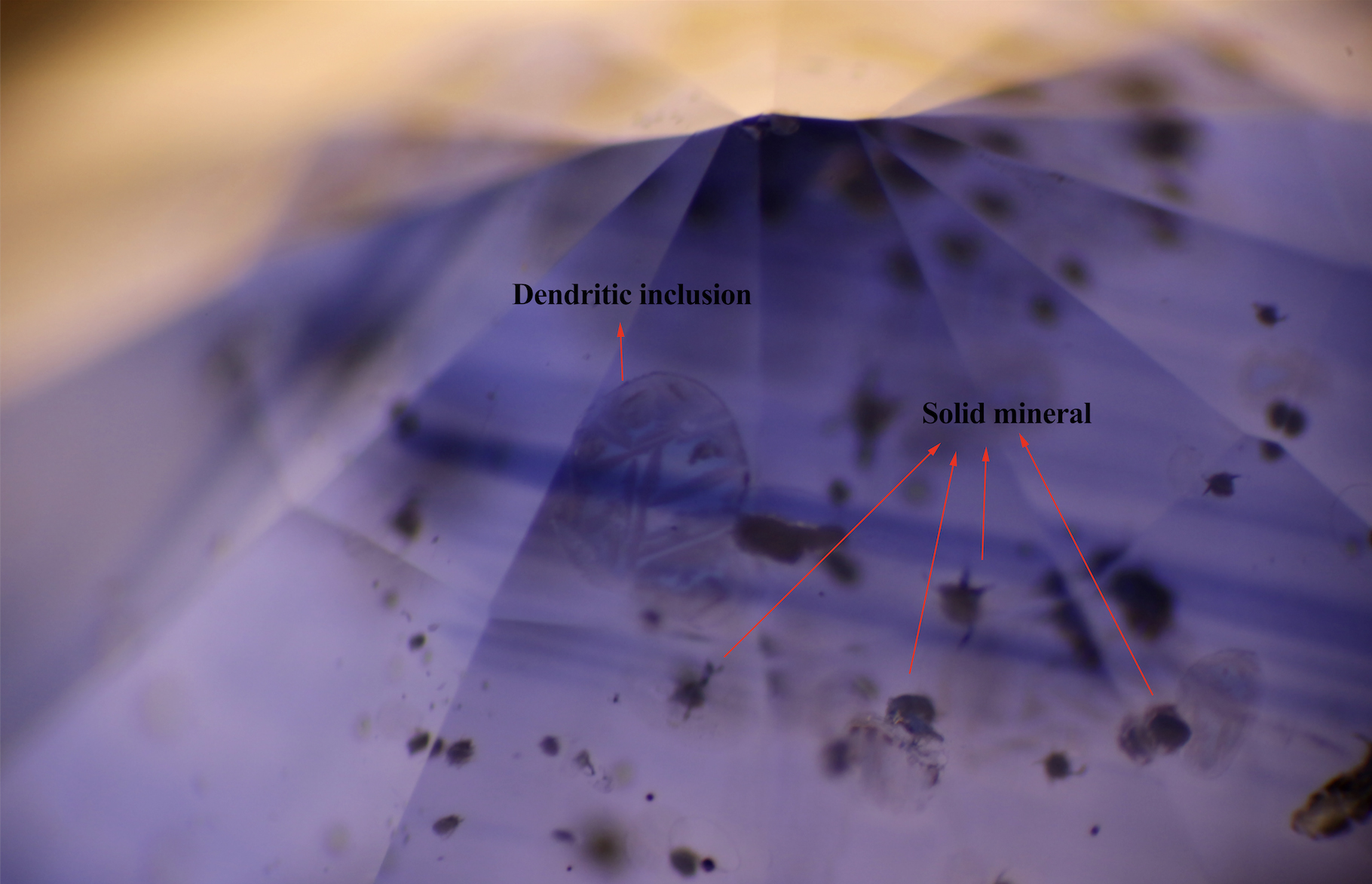

PHT (“HPHT”) treat- ment in sapphire has been a controversial topic the last few years. Recently, Guild Gem Laboratories in Shenzhen re- ceived a 7.11 ct blue sapphire (figure 1) for identification. The refractive index of 1.762–1.770 and hydrostatic specific gravity of 4.00 confirmed the stone’s identity. It was inert under long-wave and short-wave UV. Microscopic exami- nation revealed several distinct features, such as diffuse color bands and melted white solid mineral inclusions sur- rounded by discoid fractures, indicating that this stone had undergone thermal enhancement (figure 2).

Figure 1. This 7.11 ct oval blue sapphire, measuring 11.66 × 10.44 × 7.38 mm, exhibits eye-visible white mineral inclusions.

Photo by Yizhi Zhao.

Figure 37. Blurred blue color zoning and melted white solid mineral inclusions surrounded by discoidfractures. Photomicrograph by Yujie Gao;

field of view 5.26 mm.

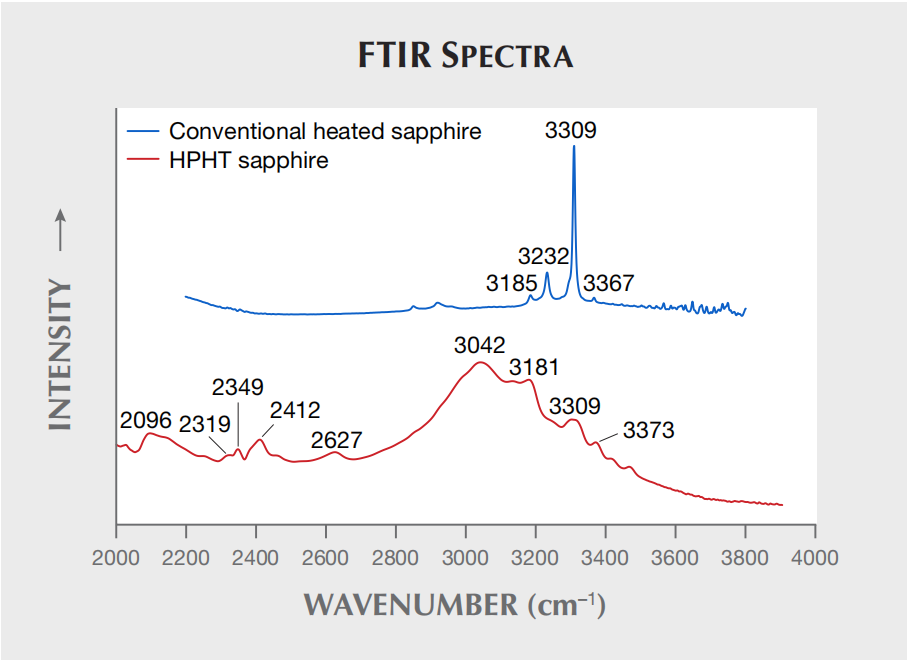

Further UV-Vis spectroscopic testing specified a meta- morphic geological origin, while energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) analysis revealed low Fe content around 400–600 ppm. FTIR spectra (figure 3) showed a distinct 3309 cm–1 series at 3181 and 3373 cm–1, consistent with heated metamorphic sapphire. We also noticed a broadband centered at 3042 cm–1, accompanied by peaks at 2627, 2412, 2349, 2319, and 2096 cm–1. According to previous reports (S.-K. Kim et al., “Gem Notes: HPHT- treated blue sapphire: An update,” Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2016, pp. 208–210; A. Peretti et al., “Iden- tification and characteristics of PHT (‘HPHT’) - treated sapphires – An update of the GRS research progress,” 2018, http://gemresearch.ch/hpht-update), the ~3042 cm–1 series band is diagnostic of sapphire treated by a high-pres- sure, high-temperature process.

Figure 3. FTIR spectra of conventionally heated sap- phire and the HPHT sapphire in figure 36. The latter showed distinct bands centered around 3042 cm–1, ac- companied by peaks at 2627, 2412, 2349, 2319, and

2096 cm–1.

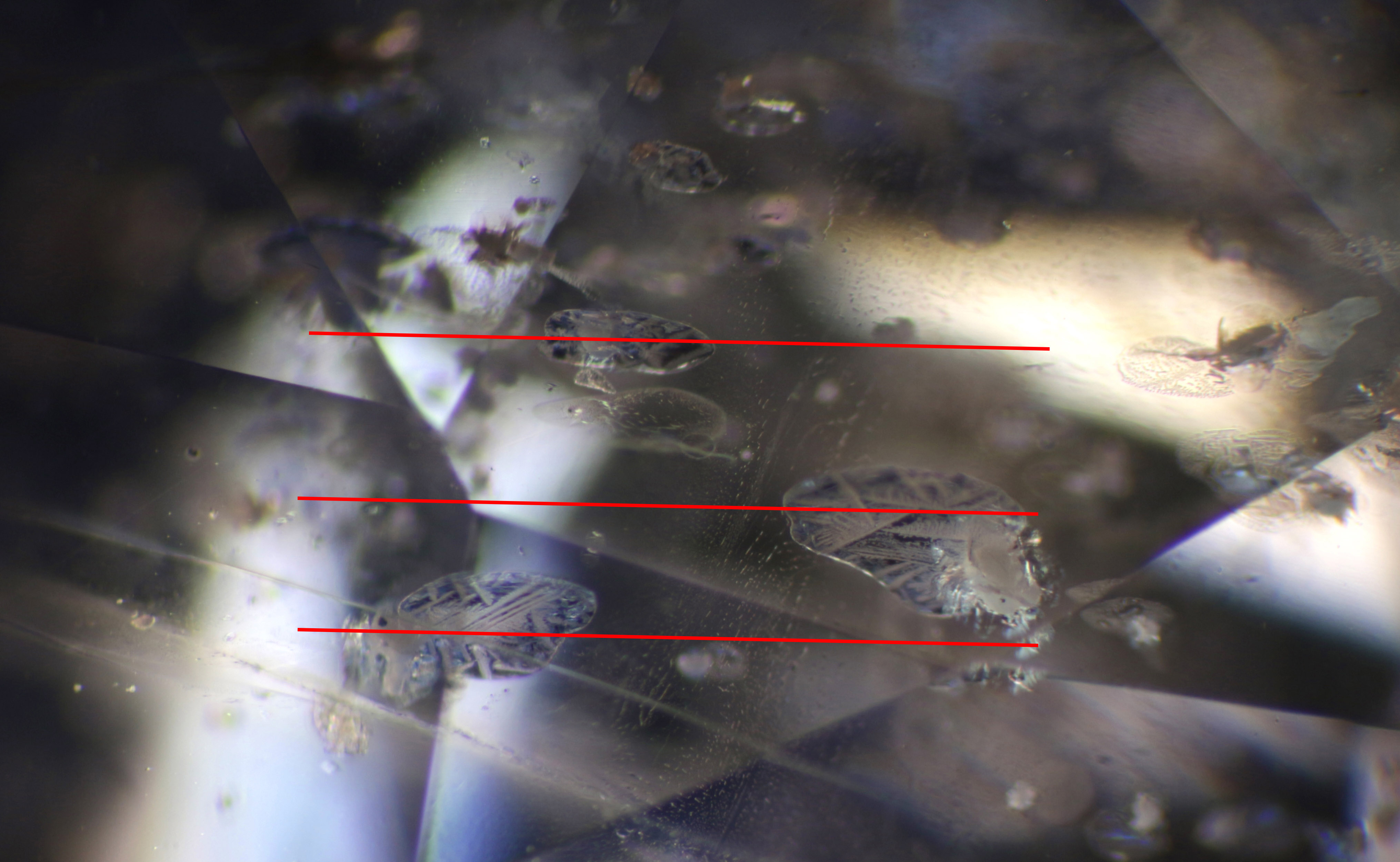

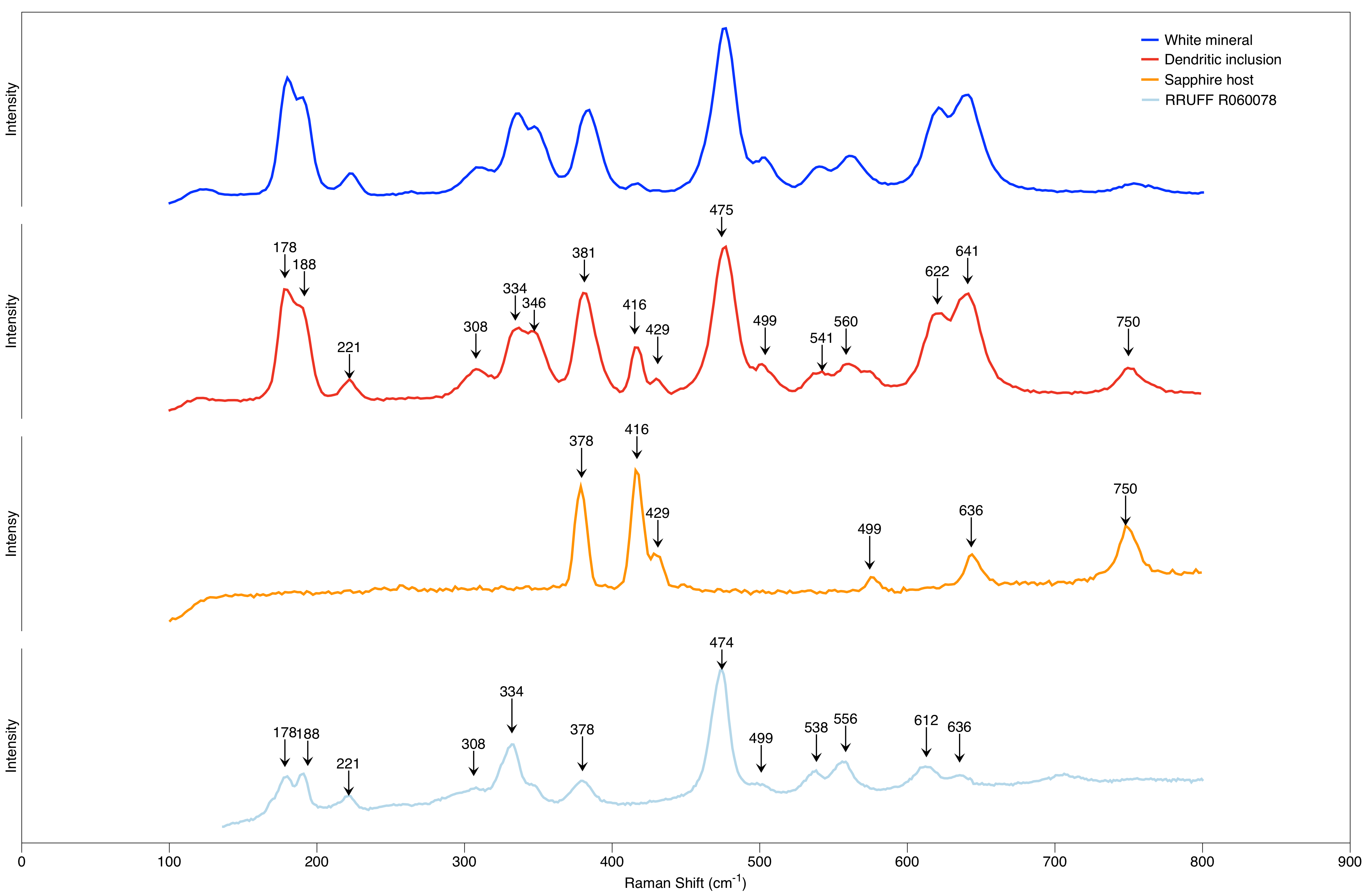

As shown in figure 4, the mineral inclusions melted and solidified within the surrounding discoid fractures, ex- hibiting a dendritic appearance. Micro-Raman spectra analysis on the white mineral and recrystallized dendritic inclusions using 473 nm laser excitation produced some interesting results. The white melted minerals and the re- crystallized inclusion showed almost the same peaks in the region of 1000–100 cm–1, suggesting that they were the same mineral. Peaks at 641, 560, 541, 475, 334, and 221 cm–1 and a characteristic doublet at 188/178 cm–1 matched with the Raman spectrum for baddeleyite (a rare zirconium oxide mineral), according to the RRUFF database, as shown in figure 40.

Figure 4. Discoid fractures were oriented in almost the same direction within the sapphire host. Photomi- crograph by Yujie Gao; field of view 2.28 mm.

Zircon (ZrSiO4) is known as a common inclusion in sapphires, which may undergo solid state thermal dissoci- ation to zirconia and silica at extreme conditions such as high temperature and/or high pressure as follows:

ZrSiO4 (zircon) → ZrO2 (baddeleyite) + SiO2

confirmed the existence of baddeleyite with zircon in heated blue sapphire by detecting a 188/178 cm–1 Raman doublet of baddeleyite in melted zircon after heating at around 1400–1700°C and normal pressure. The results of Wang et al. (2006) suggest that when using conventional heating techniques, only a small fraction of zircon trans- forms into baddeleyite, while most of the zircon inclusions keep their crystalline structure intact without any phase transformation. Based on our Raman testing, however, no zircon was found in this 7.11 ct sapphire, and spectra of both the white mineral at the center and the recrystallized minerals in the fracture were consistent with baddeleyite.

Additionally, we also noticed several fractures filled with baddeleyite in a uniform orientation (again, see figure 4). Using a polariscope and a conoscope under a micro- scope, we confirmed that these fractures occurred along the basal plane (0001) of the sapphire.

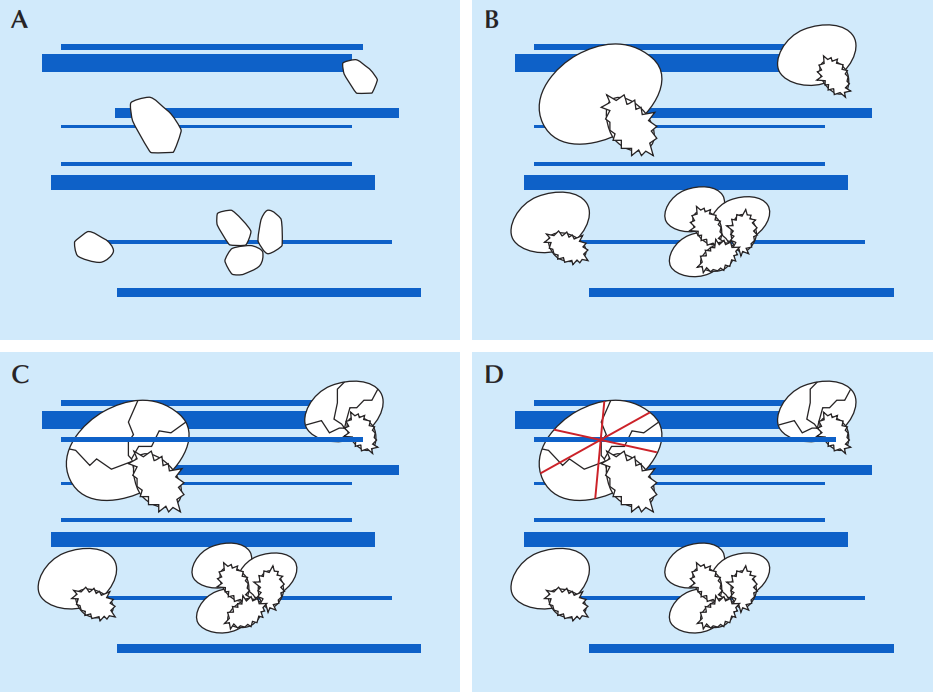

One question is whether these flat fractures already ex- isted from parting before treatment (which is commonly encountered in sapphire) or formed during treatment. It is known that parting may occur along the basal plane of sap- phire under certain situations, such as twinning or exsolu- tion of inclusions. Neither distinct twinning nor exsolved inclusions were found, and almost all of the fractures were fully filled, leaving no empty space within them. Thus, we believe that these fractures could have been triggered by treatment. The proposed occurrence and healing process of these fractures are illustrated in figure 6.

Figure 6. The occurrence and healing process of discoidfrac- tures in the sapphire during treatment.

A:Zircon inclusions and blue color bands in the sapphire.

C: Baddeleyite penetrates into the discoid and fills the fracture with no space left.

D: Baddeleyite recrystallizes in a dendritic pattern shown by the red line.

Cpyright © 2023 GUILD宝石实验室 粤ICP备粤ICP备16082724号-1号